Humans of State High

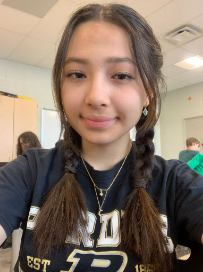

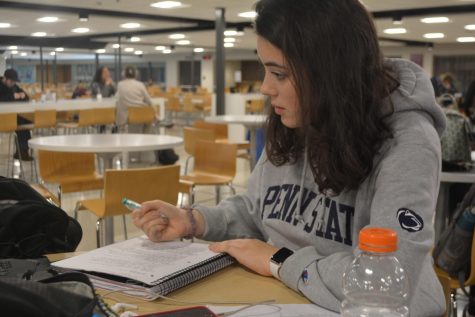

“I got diagnosed with fibromyalgia when I was fourteen, and it had just been after I moved here, so it was a really rough transition. You lose a lot of stuff from that. You lose friends because people don’t want to deal with someone who’s sick; they don’t want to deal with not understanding it. You deal with things like you can’t go to events anymore, so people stop including you in things. People don’t want to hear about it because the idea of it scares them. Like, you mention a surgery or that you’re on chemotherapy, and people suddenly don’t know how to react to you. So there’s definitely a separation socially for that.” (1/5)

“I live with JIA (juvenile idiopathic arthritis) and fibromyalgia, and living with a chronic illness—there’s varying degrees of parts and aspects of it, but it’s in no way easy, is what I just put it as. There’s a lot of challenges you have socially, school, medically, that put a lot of—they make you really gritty. You gotta deal with a lot. […] [I wish people understood that chronic illness] is constantly changing and that we have needs that need to be met, and they’re not always heard about or talked about because in my case, you can’t see them. I qualify as dynamically disabled, but most people wouldn’t see that when they look at me, because I don’t look sick, but I am. And so that’s kind of the part where I wish people knew more of what a chronic illness means and its impact on one’s life. […] You look at someone and you say, ‘I have a chronic illness,’ everyone’s like, ‘Oh, okay,’ and nobody understands the impact it has on your life and how hard it is to deal with it. ‘Cause it’s not talked about. No one talks about it on the internet, no one talks about it in social media a lot. I mean, there’s most certainly no classes that talk about it. Like, even in health class, they will mention cancer. They will not mention a chronic illness; they will not cover that topic. […] I like to view it as my chronic illness is a part of me, but it’s not something that defines who I am. It definitely has changed my perspective and how I handle situations and how I view something. It’s made me so much more empathetic to others in situations I don’t quite understand. […] I don’t automatically sit there and judge; I’m like, ‘Okay, that’s just what it is.’ That doesn’t mean that’s who they are, that doesn’t mean they’re less than, that doesn’t mean that because they have something that’s a little different that it’s [worse]. So that part of it—it makes you so much more understanding. And also, I think another big thing is it teaches you to slow down. We live in a society where everything is so extremely fast-paced. When you live with a chronic illness, you don’t have the ability to operate on the same level as other people. I live with a musculoskeletal pain syndrome, which means I have difficulty walking, I have difficulty picking things up, I have difficulty moving around, I get extremely fatigued, so stairs are a no-go. […] Not only does it mentally slow you down; it physically slows you down, and it teaches you to prioritize. Because you have—it’s what they call the Spoon Theory—you only have so many spoons in the day, and when you have a chronic illness, those spoons go fast. Say it takes a spoon to eat breakfast. It takes three spoons to drive. If you only have, like, fifteen spoons in the day, it makes you prioritize what are the most important things in your life and really focus on them. Because you don’t have time for everything, and you never will.” (2/5)

“My mom’s an OT and I’ve been in a wheelchair, and there’s such small accessibility to people who are in wheelchairs, and it’s not even something you think about. And most of the time, they’re not even clean, easily accessible; they’re back doorways that you’re like, ‘This is really hard,’ or they’re too high. It takes so much strength to push yourself up those ramps—it doesn’t even cross people’s minds. And so I think there’s a lot of that where people just don’t have to sit there and think about it. It’s just something that’s never brought up to them.” (3/5)

“[I’ve learned] how to handle people who sit in the unknown. And I mean that in a way to not get angry at people who don’t understand things. Because when someone doesn’t understand your situation and they get really mean and up in your face, it’s so hard to sit there and say, ‘You just don’t understand. You just—you don’t have it. You’re not going to comprehend that situation. And understanding that I’m not going to be able to change what I live with—that’s okay. It’s okay that I don’t operate at everyone else’s level. It’s okay that I don’t go as fast as everyone else. That is okay.’ And I also need to have compassion for other people who don’t understand those situations. Instead of reacting negatively, sitting there and using it as an opportunity to share with what I have and what I live with.” (4/5)

“[I’m passionate about] fish. I want to be a marine biologist and oceanographer, so I started out with my fascination with fish. It started in tenth grade; I worked in the aquaponics room with Mr. Lyke, and I ran the club for sophomore year. We raised tilapia and grew lettuce, and so that started the spark with my passion for marine life. I now have seven fish tanks (which my parents aren’t too happy about), but it’s something I really enjoy. There’s a great amount of serenity to it, as well as I love the science behind it; it’s something I’m very passionate about. I think animals are extraordinary because they view the world in a lens that most humans don’t. They don’t sit there and judge you. Animals (unless they’ve been treated poorly) have a great amount of trust. I think that’s something that I love about them, is when someone lives in a society where a lot of people don’t accept me, animals are so accepting, and I really love being around them.” (5/5)