Reevaluating Watergate and the 1972 Election 50 Years Later

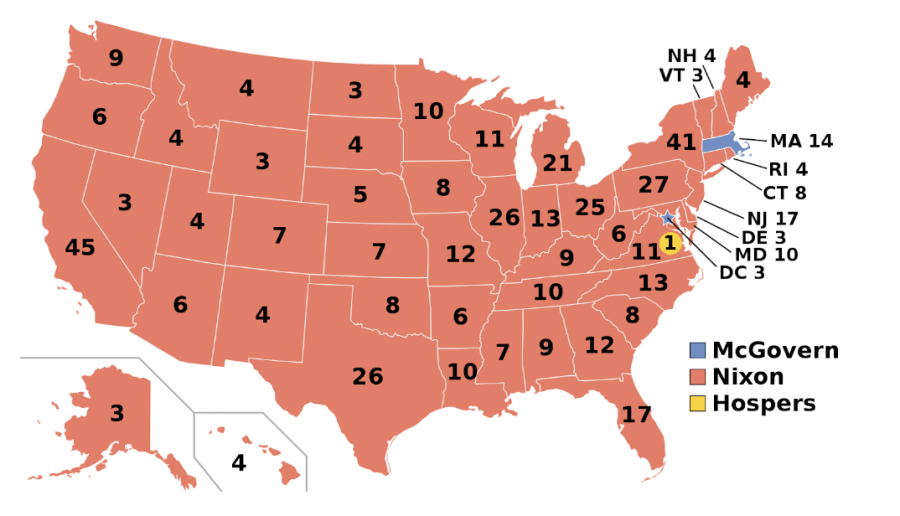

Map of the Presidential Election of 1972 between Richard Nixon, George McGovern, and John Hospers (Image from Wikimedia Commons).

November 18, 2022

On Nov. 7, 1972, the United States held the 47th Presidential election. Richard Nixon won a second term in one of the biggest popular vote and electoral victories in the nation’s history.

During his first term in office, Nixon became increasingly controversial. Abroad, he was unpredictable, launching an aggressive bombing campaign in Cambodia to weaken North Vietnam. Yet, he also visited communist superpowers such as China and the USSR as he slowly pulled American troops from Vietnam each year. On the home front, Nixon imposed a flurry of new environmental and economic regulations, initiated the War On Drugs, and attempted to undo many of the progressive judicial reforms of the 60s.

Nixon’s opponent was Democrat George McGovern, a Senator from South Dakota. McGovern campaigned on a progressive platform of an immediate withdrawal from Vietnam, abolishing the death penalty, amnesty for all draft dodgers, and an array of new and expensive social programs paid for by steep military cuts. Although McGovern’s ideas are mainstream nowadays, the Republican campaign portrayed Nixon as a cautious moderate and McGovern as a radical hippy far out of the mainstream. As a result, McGovern lost badly, winning only 37.5% of the popular vote and 17 Electoral Votes. Nixon, in comparison, won 520 Electoral Votes and 60.7% of the popular vote (Politico).

However, not all was as it seemed, and the memory of the 1972 Election is now overshadowed by an event that continues to influence American politics today. Five months prior to 1972 election day, people working for Nixon’s re-election campaign broke into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters to steal top-secret documents and bug the office’s phones. The cover-up surrounding the June break-in by Nixon’s staff resulted in a years-long investigation that would force Nixon to resign, erode public trust in government, and usher in historic oversight legislation. The Election of 1972, 50 years later, remains a valuable lens for understanding contemporary distrust of government institutions.

At State High, Brian Scholly and Brian Smith teach AP History. Their classes cover this period, which was defined by a major shift in public opinion about government.

“Before Vietnam and before Watergate, many Americans just accepted at face value what their government was telling them,” Scholly stated.

However, Watergate’s impact was quickly seen. According to Smith, “In the immediate aftermath, I feel people were very skeptical of the government and the systems. And that’s how we get to Jimmy Carter.”

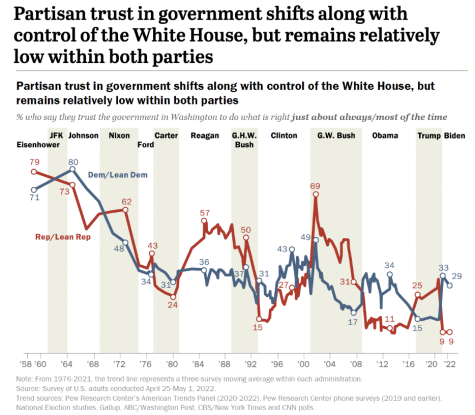

Pew Research Center’s long-term survey data on public trust in government reinforces Smith’s point (PEW). As the chart below shows, trust increased with Carter after a steep fall with Nixon.

Scholly added that President Ford’s pardoning of Nixon also contributed to the decrease in trust because the people believed that the government was unwilling to hold its elites accountable for their actions.

“A lot of the American public was really hoping to find out all the details for what happened. And I think Presidents Ford’s pardon made them kind of skeptical, ‘Are we really gonna hold this guy accountable?'” Scholly pointed out.

Professor Mary Stucky, the Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Communication at Penn State University, has written ten books on modern US presidents. Although Stuckey agreed that Watergate was a huge breach of trust, she revealed that Watergate was not the only source of distrust at that time.

“There is no question that Watergate affected public trust. It would be a mistake, though, to blame it all on Nixon – it was Watergate plus Vietnam – and LBJ gets a share of the responsibility there as well,” Stuckey wrote in an email.

As the PEW chart shows, during the late 1960s, trust in the government declined dramatically. After a series of Civil Rights and economic victories in the early-mid 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson plunged the nation into an unpopular war. In context, Watergate worsened the distrust rather than created it.

In response to the growing distrust, a series of important laws were passed to address the ethics violations of Watergate in the remaining decade.

Smith pointed to 1974 amendments to the Election Campaign Act, which created the Federal Election Commission to monitor campaign spending.

“It’s been since watered down a little bit with certain court cases, but that’s definitely a big one,” Smith noted.

For Scholly, the 1978 Ethics and Government Act was a necessary reform because it ensured that elected officials were “doing things by the books” through ethics requirements like financial disclosures.

“I’m sure you’ve heard the phrase, follow the money when it comes to Watergate and how that’s how it was found out. So again, the idea that things were a little more opened up through this ethics and government act was a positive reform,” Scholly stated.

Stuckey echoed Smith’s emphasis on the positive legacy of the Election Campaign Act but also referenced some broader impacts, particularly related to Congress.

“A lot of people overlook the effect of Watergate on Congress. 1974 was a HUGE new class of representatives, and they made a lot of changes. Congress became more open, but also harder to manage,” Stuckey wrote.

In addition, Watergate transformed the role of the press. According to Stuckey, “Pre-Watergate journalists were very much on the side of politicians. Watergate made investigative journalism a thing. Journalists quit trusting officials and their cynicism got transferred to the news. They lost deference. They started looking for corruption. So more accountability but less trust.”

In addition to the importance of investigative journalism, Scholly and Smith also emphasize accountability as a key legacy of Watergate.

“Nobody, not even the president of the United States,” Smith noted, “is above the law.”

As Sholly concluded, “Even at the most powerful positions in the world, you’re gonna be held accountable if you break the law.”

So what does this mean for us today? How does this apply to the current political climate? Certainly some similarities are visible. For one, politicians are being held accountable for their actions through Congressional Hearings. The January Sixth Committee Hearings have been compared to the Watergate Hearings for their impact. A key difference is that the trust in government in 2022 is, according to PEW, lower than it was following Watergate. The PEW data does offer some reassurance, however. Public trust in the government can be repaired. The voting turnout among young voters in the 2022 midterm elections last week suggests that collectively, Generation Z (Or Zoomers for short) may be up to the task.