The Deepened Disasters of Hispania

October 30, 2022

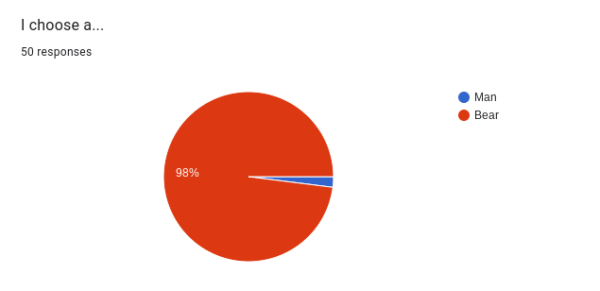

Hispanic heritage month, created by the US in 1968, has long been sold as a time to honor and celebrate the Latino community. Despite the designated month, when it comes to real issues affecting us, white America chooses to look away.

The Latino identity is a strong one. Regardless of our country of origin, Latinos feel a sense of community and pride in their culture. However, when reframed in a Western narrative by imperialists themselves, what it means to be Latino is quickly lost in translation. While the Hispanic community has been stomped into the ground and continues to suffer, suburban moms everywhere take pleasure in Taco Tuesday. From gross misrepresentation in school curriculum to stereotypical costumes, a month that was once meant for celebration has been appropriated by humiliation.

Our realities lack portrayal and our cultures are abundantly overtaken by those who are not understanding of our lives. We are stigmatized for our own traditions, but America loves Cinco de Mayo, margaritas, and burritos?

The negligence which the US government perpetuates against Latinos is indeed not limited to those living the Latino reality within its borders, but rather also steps onto the international playing field: Latin American countries and their people are left to mourn their long history with the US’ harmful international tactics every day, living exploited and forgotten.

To have used this month the right way was to take some time to listen — some time to understand.

Here, we explore the harm inflicted upon our countries by nature and by humanity.

Mexico – Elena Wright, Opinion Editor

September 19 is a notable day in Mexico City or, “Chilangolandia”, and beyond. Just three days after Mexico’s independence day, September 16, the 19th contrasts the celebration with memories of destruction and tremendous loss.

Early morning of September 19, 1985, Mexico City and surrounding areas near the pacific coast were hit by a magnitude-8.0 earthquake. Though it originated in our around the state of Michoacan, the damage was concentrated in Mexico City–affected most negatively due to the topography of the area. Built on a dried-up river and Aztec ruins, Mexico City finds itself uniquely vulnerable to this natural disaster.

Effects of earthquakes and general ground movements have over time created some, askew structures. The Zócalo, the main plaza in central Mexico City, also the site of the main ceremonial center of Tenochtitlan (capital of the Aztec empire), is neighbor to a rather crooked Spanish cathedral. The sinking of the earth over hundreds of years has left this relic of colonization leaning on its side.

The 1985 earthquake changed how Mexico viewed natural disasters.

The official number is 10 thousand. 10 thousand deaths as a result of the temblor. Many believe the number to be several times that. Loss of all electricity including traffic lights and public transportation compounded the devastating effects of 30 thousand flattened buildings and many more damaged. My aunt’s house shifted and had a crack open up in the middle of her floor.

Guadalupe D’anda, my mother, lived in northern Mexico for most of her life.

“It was the first time there was serious structural damage. The house came up in the middle and it split a little bit,” D’anda said, describing the damage to her sister’s home.

My uncle is a pediatrician, and at 7:18 am when the earthquake struck, he was on his way to work at one of the largest pediatric hospitals in the city. The hospital collapsed, leaving loss and chaos in its rubble.

“Instead of working like normal, he began rescuing his colleagues, patients, and their family members. There were a lot of deaths,” D’anda said.

250 thousand people were left shelterless and the city found itself in complete total crisis.

Soon, however, the city began to heal and reconstruct what had been lost. Of course, the poor were and continue to be disregarded when it comes to their safety. Roughly 60% of the city is comprised of unregulated, not up-to-code, high-risk areas. Unfortunately, the city and its people remain vulnerable despite the millions spent by uber-rich man, Carlos Slim, on development projects.

Just six years after the catastrophe of 1985, the city’s public earthquake alarm system became active. Giving rough 60 seconds of a warning, the alarms allowed people to get a head start on evacuation–saving countless lives. In an earthquake situation, 60 seconds can be the difference between life and death. At school, rather than monthly fire drills, we had an annual earthquake drill on September 19. On this very day, the doomsday sounding alarms sound throughout the city, and everyone exits work or school to as open of an outdoor space as possible. In a city with over 20 million people, this is usually a road.

“They live with the constant fear of a terrible earthquake again, one that destroys houses and buildings,” D’anda said. There is no earthquake season. They can occur day or night,in rainy or dry seasons. Chilangos live day to day never knowing if another catastrophe will strike.

September 19 marks the date of two more destructive earthquakes.

On the 32nd anniversary of 1985, September 19, 2017, Mexico saw yet another quake bring death and destruction. Coming from the state of Puebla, the 7.1 earthquake caused at least 200 deaths, and of course, many injuries to people and buildings.

On the 37th anniversary, yet another earthquake, this time a 7.6 earthquake from the pacific coast of the country, killed two. Due to the earthquake simulation on the anniversary, many were not sure if the alarms sounding across the city were truly signaling danger.

Oddly enough, September 19 has no increased chance of being hit with an earthquake than any other day. Science simply cannot explain it. The chance of three destructive earthquakes occurring on the same day is between 0.000751% and 0.00000024%–essentially, zero.

Earthquakes are deeply tied to Mexico City and its people’s culture, history, and, personal lives. Virtually every family in the city has some shared experience from 1985 and beyond. The earthquakes left the city in pieces, but people found themselves more unified than ever and began to put the city back together.

When the authorities and government found themselves overwhelmed and unable to help adequately in 1985, civilians sprang into action.

“Society organized spontaneously, incredibly, in solidarity and in a very organized way,” D’anda explained.

Los Topos (the moles) pulled people out of the rubble and made sure they received help, putting their own lives at risk in the process.

“It was a unique example. Not only in Mexico but in all of America nothing has been seen like it,” D’anda said.

Los Topos have since provided aid to virtually every major earthquake in Mexico as well as across the world. Since 1985, they have helped Japan, Colombia, Haiti, Nepal, and Indonesia with tsunami and earthquake destruction. Los Topos even assisted Miami in June of 2021 when a condo collapsed–helping in search and rescue efforts.

“There is a historical memory that you can do something. Even with all of the adversity, a bad government, and lack of resources, they are still capable of saving many lives,” D’anda said.

Earthquakes have shaped the city and country in immeasurable ways, but it has also provided unity and proved that in times of need, Mexico shows up for one another.

Puerto Rico – Elisa Edgar, Managing Editor

Tropical Storm Fiona touched down on the island of Puerto Rico on September 17th. I haven’t heard from my family living there since. Just a few days after Hurricane Ian hit Florida, causing mass power outages, power has been restored. It’s been weeks since Category One Hurricane Fiona hit Puerto Rico, and yet, island residents have been left in the dark- both literally and figuratively.

There has been a systematic differentiation in the treatment of the island compared to the mainland, even though Puerto Ricans are legally US citizens.

Some parts of the island were flooded with up to 30 inches of rain. This amount of rain causes flash flooding which triggers mudslides, leaving the island without power. Emergency crews rescued over 400 people from the Ponce region, which was hit hardest with rain. However, at least 25 deaths related to the hurricane have been reported thus far. It is important to remember that in the past, death and injury counts coming out of the island have been misreported or warped to protect governmental reputation.

More than 270,000 clients out of 1.47 million were without power, over 900,000 residents are still without power. The loss of power has made it impossible for hundreds of schools to open for the school year even still. Businesses like grocery stores and gas stations also closed, all of which are necessities that cannot be overlooked. Many residents are still feeling the effects of the last damaging hurricane to rip through the island- Hurricane Maria. Puerto Ricans live in a constant state of fragility. Even while many have been without power for years since Maria, they are yet again hit with more damage and minimal assistance. Hundreds of thousands are still without water, more than 100,000 clients out of 1.2 million are without water service. The total damages of the hurricane are still yet to be seen, yet experts predict a multi-billion hit to the economy. It will undoubtedly trigger an economic crisis in an already unstable economy.

My mother, Koraly Pérez-Edgar, was born in Puerto Rico. She often laments the suffering her family on the island must experience, along with everyone else there. However, the story of Puerto Ricans is one that has been refused to be defined as a sob story. Even in the face of oppression and imperialism, Puerto Ricans retain strong pride in their culture.

“We are fiercely proud of being Puerto Rican. People joke that we will put a flag on anything,” Pérez-Edgar said. “We see ourselves as being resilient even in the face of repeated hardships and roadblocks. We will go into the streets if needed to have our voices heard. We cope through dark humor. We love our music and food and wish more people knew about the contributions we make to society.”

This continuous marginalization is easiest to see visually during natural disasters. However, it extends far beyond hurricanes, and far beyond the present day. This differential treatment started in 1898 with the annexation.

For example, the Jones Act limits what type of goods can be directly shipped to PR and how they are taxed. The Jones Act was put into place in 1920, yet the effects still remain even today. Every now and then, the US will waive the act temporarily, such as after Hurricane María in 2017. Nevertheless, they have refused to repeal it. As a result, items to be purchased for PR have to be sent to the mainland (say Florida) and then go to the island. It’s taxed twice because of that, along with the added costs of the extra shipping. Occasionally, there are also limits on what the government or individuals can purchase creating virtual monopolies.

“We barely recovered from María and the infrastructure is not in place,” Pérez-Edgar said. She described her dismay when hearing the news of Fiona. “The same limitations that prevent rebuilding are still in place now. Indeed, they were debating waving the Jones act so we could get generators. The fact that it has to be debated is maddening. Electricity is spotty and it is not clear when general infrastructure will be up and running. The devastation was not as bad as María, but that is because María was catastrophic.”

When it comes to government services, there are huge discrepancies in support. For example, Medicare and Medicaid on the island will reimburse for fewer procedures or at lower costs, versus the very same care if you were in Georgia. Each little thing adds up so that life is harder on the island. A task that is easy to complete on the mainland becomes days and days of bureaucracy, with fewer results to show for it.

One of the first steps towards making daily living easier on the island would be to remove the bureaucracy Washington has imposed on Puerto Rico.

“They have to remove the Washington imposed restrictions on what companies can do, how individuals can help, and how things are run. For example, the US imposed a private company, LUMA, to take over electricity. Rates have skyrocketed and service got worse. But, people have no power to complain because it is mandated. It’s not like here, where you can shop around for electricity providers. You may need something like a Marshall plan that is coordinated, systematic, well-funded, and led by the voices of the people with boots on the ground,” Pérez-Edgar said.

This month, while I celebrate my “Hispanic Heritage”, thoughts of my people loom in the back of my mind. This year, instead of buying skeleton decorations or buying Fiesta Mix for the family, money can be better spent towards victims of this disaster. Donating to mutual aid groups or other effective organizations can and will save lives. Some resources have been provided below.

Brigada Solidaria del Oeste is a mutual aid group asking for donations of emergency essentials for residents, including first-aid kits, water filters, solar lamps, and water purification tablets. They also welcome monetary donations as another form of direct aid and support.

Global Giving is a non-profit organization that has launched the “Hurricane Fiona Relief Fund” to fund first responders providing emergency resources to island residents.

Hispanic Federation is a non-profit organization that is providing emergency resources to island residents.

Colombia – Eloise Dayrat, Editor in Chief

Colombia is a rich country. We have la selva del Amazonas and La Guajira. We have the Andes mountains, home to los frailejones. And, we have coral reefs. But in being so rich, we are quick to forget our wealth. Some spaces are overlooked.

Varadero reef is one important discovery in the marine world. The reef is located in the center of the Bay of Cartagena, a highly trafficked area by trade boats and tourist transportation. The very existence of a reef in such a location is incomprehensible. Like any other photosynthesizing organism, corals need sunlight, something that has a high variance of where Varadero is located. The reef is right at the opening of the bay and so it receives fresh ocean water, granting it enough light to survive.

The Cartagena Bay waters were once crystal clear, with reefs stretching from one end to the other. Slowly, industries took over in the Canal del Dique.

With the destruction of reefs comes the loss of entire ecosystems. Said ecosystems sustain some of the most vulnerable populations in Colombia. The island of Tierra Bomba has multiple small towns, one of them being Bocachica.

Bocachica is primarily afro-descendant and receives little to no support from the government. Education levels there are low, fresh food imports are non-existent, and there is no trash collection; el abandono del estado. The town survives off fishing. It is used both as a food source and as a way to sustain their economy.

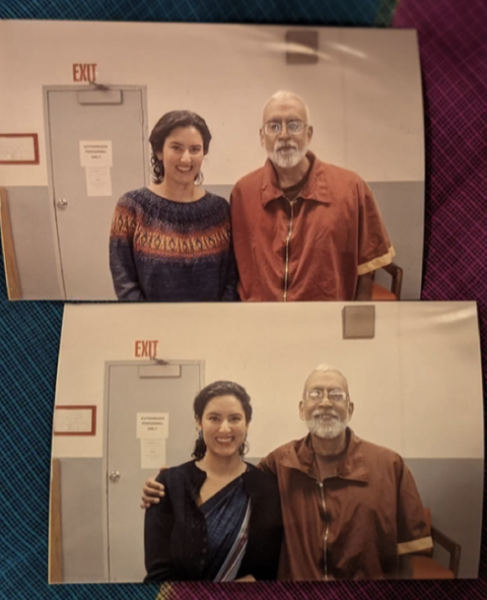

My mother, Dr. Mónica Medina, has spent almost ten years working on the reef and with the local community. She was invited to give a lecture at the Latin American Zoology Congress years back. There, Valeria Pizzaro and Mateo López-Victoria mentioned the reef to her. She had funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to be used toward studying the microbiome of corals.

“We had to go across the entire Caribbean [with these funds], I made Cartagena one of the target sites alongside Curaçao and Panama,” Dr. Medina stated. A colleague’s team went to Curaçao and one of Dr. Medina’s grad students took a team to Panama while she worked with Pizzaro and López-Victoria, among others, in Cartagena. From a study of the reef, she realized it was an interesting place to study and once again got funding from NSF, this time to study Varadero itself.

“We realized that the microbiome which Varadero holds is different from that of the Islands of Rosario, the neighboring national park. This as well as the quality of lighting in comparison to the park,” Dr. Medina said.

She describes Varadero as the “last man standing”. Dr. Medina said, “The bay has been highly deteriorated. There once were reefs in the entire bay, and now the only thing remaining is Varadero.”

In 2013, the discovery of Varadero at first was conceptualized as a revolutionary finding. Scientists believed the secrets behind its survival to be the key to saving the world’s reefs as pollution increases and water quality decreases. While this came to not be the case, Varadero reef is the last survivor stemming from the previously vast amounts of coral in the bay.

“The reefs are in the periphery of the impact. It’s in the cusp of the Bay of Cartagena which is called Bocachica. And there, oceanic water, clean water, comes and light is able to penetrate. However, when there’s a lot of water coming from el Canal del Dique into the sea, the turbulence of the water covers the reef. So there’s a very high variance of light penetration and this is what has permitted it to survive,” Dr. Medina explained.

Though, with such rapid changes in our climates, Varadero is just as vulnerable as the rest of the world’s reefs. Such harsh contamination in Cartagena’s bay comes from the entire country.

“It’s the Magdalena river. It’s the nation’s biggest river that comes all the way from the Andes. It brings all industrial residue and waste to the canal. And this is in addition to the waste coming from the city,” Dr. Medina evaluated. The waste mentioned coming from the city is categorized into multiple things, one being the industry and movement of cargo ships, as the canal is a huge trade point for the county.

Of utmost relevance to Dr. Medina’s project and story is the community of Bocachica. A town of fishermen rich in history and Afro-Colombian culture.

“Throughout our process, we needed lanchas [speedboats]. Bocachica – and Tierra Bomba in general – is a place of primarily afro-descendant communities who are very poor. We met a family who has turned into our support. They’re the captains of the boats which we always use and across them, we’ve been able to access a very closed community to people coming from the mainland because they don’t trust anyone. This is in big part because of the abandonment they’ve faced from the government and from the greed people hold,” Dr. Medina said.

The people of Bocachica are people of warm and welcoming hearts and minds. Despite their love for their country and culture, they are left behind by the government, kept away from resources. Beyond this, the rich are exploitative toward their land, as Dr. Medina mentioned. They buy land from the community at unfair prices, take on major construction projects to build luxury hotels and tourist attractions, and turn an ignorant, blind eye to the disasters formulated and aimed at the communities whose land was essentially taken from them.

“As a result of working so much with los lancheros and their family, we’ve been able to get to know the community more and more each time. We’ve been able to do many projects, with funding from Fulbright and Penn State, with the community for education and to teach them what they have at their hands; how to sustain it and protect it,” Dr. Medina continued in explaining the connection between Varadero and Bocachica.

Now, the most important step is restoration. Not only in Varadero but in the rest of the world. Dr. Medina is working in collaboration with Dr. Oren Levy and professor Ezri Tarazi, two prominent Israeli academics. She is also aiming to teach the community how to participate in the restoration project.

The value of Varadero is additionally seen when taking into consideration the following that Dr. Medina said: “The Colombian government wants to implement a cleaning project in the Cartagena Bay to capture the sediments from the Canal del Dique, which will clean the waters. However, if we don’t have anything to replicate and place across the bay there is no way of restoring the bay as they aspire to. When we restore new sites across the bay, the larvae of the corals and organisms in Varadero can colonize said new sites. They will be accessible for the many species once the water is cleared up as there will be light.”

For Colombia, restoring Varadero must happen because it is “an emblem” to the world, as Dr. Medina placed it. “It is an emblem to marine conversation around the world,” she said. “Science Magazine covered it and Valeria and Mateo’s cause. As a result, global journalism took it into its hands in expectation of it being as revolutionary as we assumed it to be in the beginning. So many articles were written and translated into many languages.”

Now, for the restoration, Dr. Medina is in communication with the Colombian government and environmental NGOs (Cardique and EPA) to figure out order; academic standings, timeline, and funding. Also, private allies have been made. From this, Varadero’s project is one against the standings of parachute science. “North American and European scientists have long practiced showing up, collecting samples, then leaving and leaving nothing with the communities they go into. We’ve been careful because we are Colombian and we want to watch the resources of the community and the nation because it’s theirs. They aren’t mine.”

They were once going to get rid of Varadero in the name of private stakeholders’ wishes and unknown corporate interests. At one point it was speculated that Varadero was poisoned, though no hard evidence is held. The reef is a sign of resistance. All came united for the cause of taking care of the reef; the people, the NGOs, the government itself, the scientific community, and the local community. Varadero is an emblem.

To know more about Varadero and Bocachica, watch the documentary filmed on the community, Saving Atlantis. The film features Dr. Medina among many other scientists, as well as locals.