In the 2012 Comedy, “The Dictator”, comedian and actor Sacha Baron Cohen plays Aladeen, the dictator of the fictional country Wadiya, who visits the United States. The character serves as a caricature of oppressive dictators, as to represent their flaws and stupidity tenfold through comedy and over accentuated costume and dialogue.

“The Dictator” is an example of satire. Satire is the use of humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices. Satire is often used in forms of media (i.e., movies, television, books) as a commentary of relevant topics or people. While satire can be effective, its message can be misconstrued and taken the wrong way, often leading to negative reactions to the satirical piece or—on the extreme side—adoption of satirized ideologies and perceptions.

Thus begs a question about the usage of satire and its effectiveness: whether or not the message outweighs misconception and whether the content is worth representing on screen or on paper.

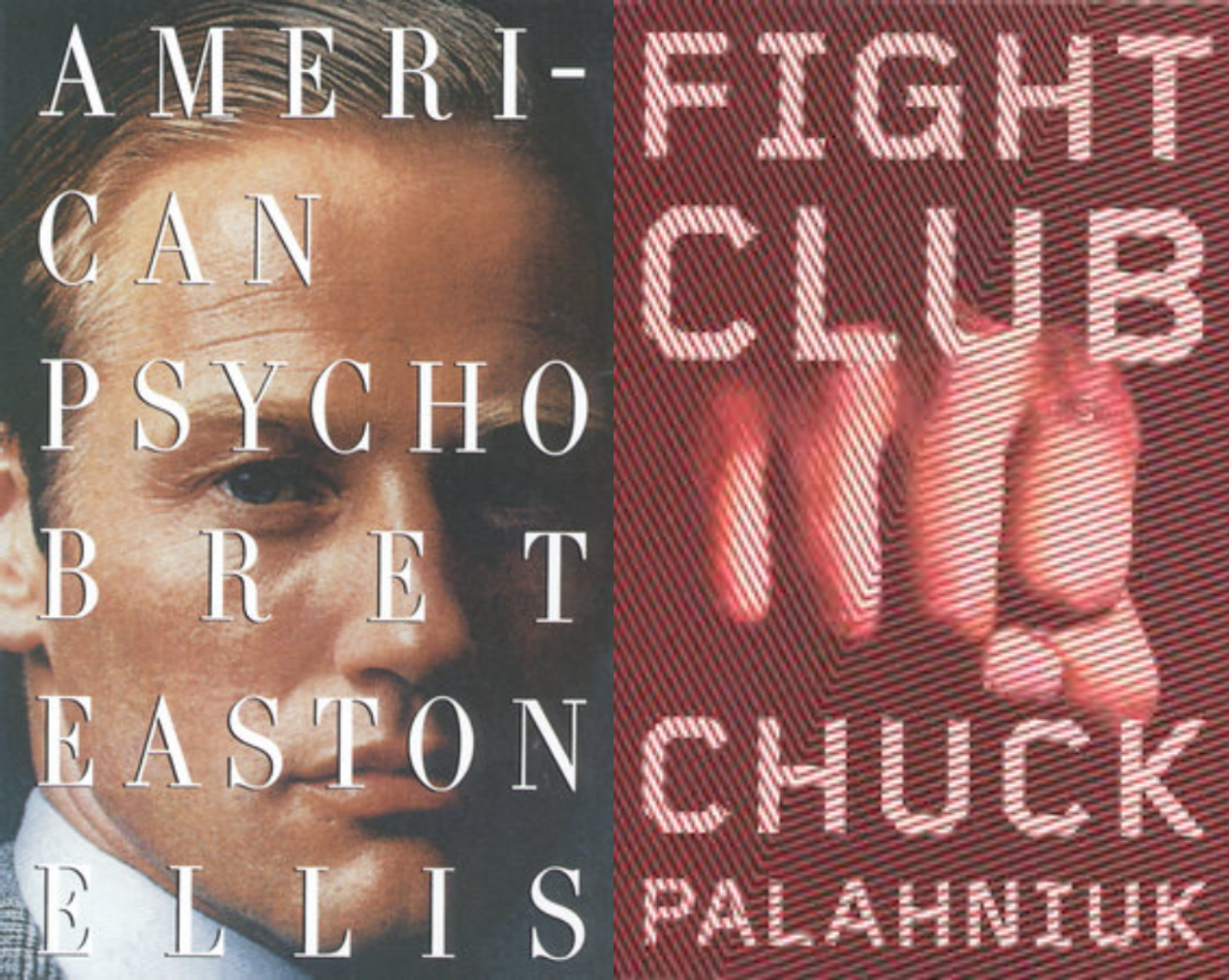

“American Psycho” and “The Last Party”

“American Psycho”, originally a 1991 novel by Bret Easton Ellis, was adapted in 2000 by Mary Harron in her 2000 thriller by the same name. The movie follows Patrick Bateman, a Wall Street Investment banker who is a sadistic psychopath. He is flagrantly rich and pompous, while he indulges in murder and serial killings.

Christian Bale, actor who portrays Patrick Bateman, spoke out on his thoughts on the character and its legitimacy in his 2022 GQ interview.

“Clearly, it is a satire on capitalism in the eighties and, as such, is so bloody far fetched and ridiculous that, to me, I can’t help but think it is hilarious,” Bale said.

Bateman is a direct satirization of Wall Street: one who doesn’t care for the lives of others and only cares about his own wealth, status, and ego. The satire is executed to criticize Wall Street and explore the implications of inhumanity and lack of empathy in a greater society.

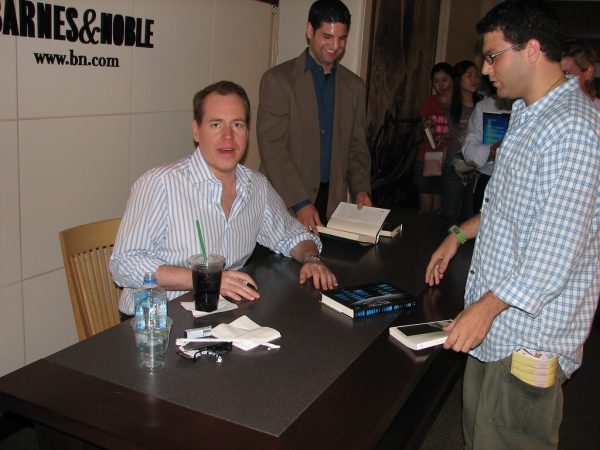

Credits to Flickr

Bret Easton Ellis originally researched for the 1991 novel to be about the men on Wall Street, but diverged from this, deciding to write on how out of touch and hedonistic the men are.

“It was going to be kind of like “Less Than Zero” [Ellis’ 1985 novel that follows Clay, a rich college student who falls into drug- and alcohol-induced escapades] set on Wall Street,” Ellis said in his 2016 Ora interview. “I’m going to follow a young man… I was hanging out with these young guys who were working on Wall Street and doing research…I just saw this parade of status one upmanship: who has the best suit, who has the best house in the Hamptons, who has the hottest girlfriend.”

Ellis’ intentions with American Psycho were clear—to delve into the problems of Wall Street while presenting it through the lens of the psychopathic serial killer. Like Ellis does, it is important to criticize institutions and point out flaws in order to define the root of a problem. In his 1993 political documentary on the 1992 presidential election, “The Last Party”, Robert Downey Jr. visits Wall Street and outwardly criticizes it.

“If money is evil, then that building is hell,” Downey Jr. said. “This is the most obnoxious group of money-hungry, low-IQ, high-energy Jack Rabbit, f***ing wannabe-bigtime, smalltime s***-talking, bothersome, irritating, immature motherf***ers I’ve ever had to endure for more than five minutes.”

In the context of a documentary like “The Last Party”, where the purpose is to give information at face value and provide a way to view otherwise inaccessible information, opinion and advocacy are easy to be seen and interpreted in their original form. However, the implied nature of satire/satirical pieces often leads to misinterpretation. In the case of American Psycho, Christian Bale similarly visited the Wall Street Trading Floors and was able to talk to the traders.

“I got on the [Wall Street Trading Floors] and a bunch of them were like, ‘Oh, Patrick Bateman!’ and they were patting me on the back going, ‘Yeah, we love him,’” Bale said. “And, I was like, ‘Ironically, right?’ and they were like, ‘No.’ So, it was always worrying.”

Bale’s interaction with the Wall Street Traders represents the potential danger of satire. Due to it being the undertone, satire may not be interpreted as criticization and, in this case, as an endorsement.

“Fight Club”

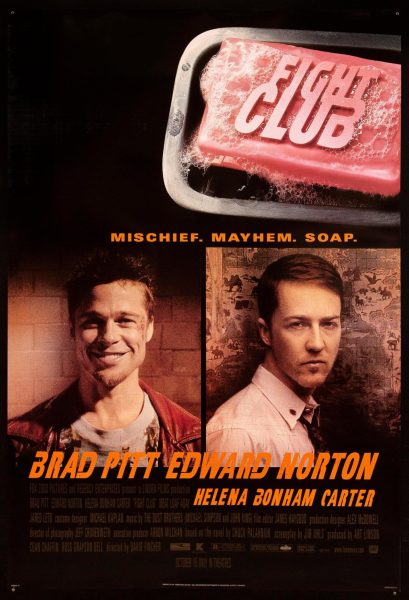

David Fincher’s 1999 film, “Fight Club”, was adapted from the 1996 Chuck Palahniuk novel. The film promotes anti-materialism and satirizes hypermasculinity and consumerism. The Narrator (Edward Norton) serves as the “everyman” and remains unnamed for the entirety of the movie’s runtime. To cure his insomnia, The Narrator goes to support groups, namely a testicular cancer support group, despite not having any illnesses. He views the actual attendees as lesser, finding superiority in the “emasculation” of the other men.

The Narrator meets Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), the idealized version of The Narrator. The two start an underground fight club, which evolves into Project Mayhem, which grows from petty vandalism to domestic terrorism. This arc, of a man “down on his luck” to the terrorist leader, is a direct satire of how destructive tradition and hyper masculinity can be.

The satire serves to support the allegorical narrative of homoromanticism and repression of male sexuality. The famous line from the film, “The first rule of Fight Club is you do not talk about Fight Club,” represents notions about being closeted and repressing your sexuality. Palahniuk’s novel is often represented as such. Tyler Durden, who is ultimately revealed to be a figment of The Narrator’s psyche, is a projection of The Narrator’s views and what it means to be a man.

If the satire and allegory of the film serve to criticize notions of hypermasculinity and shame idealizations of people like Tyler Durden, why is it that “Fight Club” is often supported by the same groups it is shaming?

State High Film and Media Teacher, Jared McConkey, describes this as a logical fallacy.

“When you mix [agreement with anti-materialism] with the hyper-masculinity and the aggression and things like that,” McConkey explains, “it almost becomes like stepping stones that, ‘I agree that I’m more than the things I buy and so, if I agree with that idea Tyler Durden expresses, don’t I also agree [with the other messages?]’”

This dramatic acceptance of idealization is reflected in the news. In 2009, Kyle Shaw, was arrested for an attack on a Starbucks in New York. The 17-year-old attributed the attack to Tyler Durden. Shaw created his own fight club in the city and called the attack “Project Mayhem”.

This example, while extreme, gives insight into how satire can be misinterpreted. Some people miss the criticisms, whether out of ignorance, overlooking, or both, and begin to emulate the ideologies. In Shaw’s case, he disregarded the undertones of the film and sought to act on the beliefs represented.

Satirical Representation

Satire matters.

If we fail to make criticisms of the past or of present institutions, people, or ideologies, we will fail to recognize/communicate their flaws and fix them. Satire being an undertone gives way for conversation beyond the surface.

Satire is important.

Satire is only as effective as the audience makes it. While satire is important, it goes hand in hand with media literacy. The understanding and conversation is driven by the audience’s ability to pick apart and delve thematic messaging, going beyond emulations of the surface.

Satire is necessary.