From Nov. 30 to Dec. 12, 2023, the United Nations member countries met in Dubai to discuss the growing climate crisis at the 28th Conference of Parties, or COP28. The event became subject to controversy immediately, as climate activists criticized the influence of fossil fuel companies and were appalled that the UAE, one of the world’s biggest oil-producing countries, hosted a conference designed to phase out fossil fuels.

Swedish Climate Activist Greta Thunberg harshly criticized the outcome, calling the COP28 deal a “stab in the back.” However, some concrete agreements were made during the conference — most notably, a formal agreement to transition away from fossil fuels and triple renewable energy generation by 2030.

COP conferences host diverse stakeholders, such as member-state politicians, scientists, industry leaders, climate activists, Indigenous peoples, and journalists. Of the over 70,000 attendees at COP28, government delegations and energy industry representatives both played vital roles, given that the UAE hosted the conference.

State High Environmental Science teacher Kimberly Faulds thinks government delegations are decisive for combating climate change. “Governments are key to establishing the goals to mitigate, adapt, and lower greenhouse gas emissions. And so what I think they need to do is use the power that they have as a collective to work with industry and defossilize our economy and societies,” Faulds said.

John Donoughe, another State High Environmental Science Teacher, agrees about the vital role governments play in the global climate crisis. “They have to play a role if it’s going to be addressed. I don’t see any other way.”

He also acknowledges that countries have wildly different approaches to tackling climate change as well as different systems of government.

“We have to be careful,” Donoughe stated, “because not all governments are created equally. The United States, for that matter, might be a lot different than North Korea.”

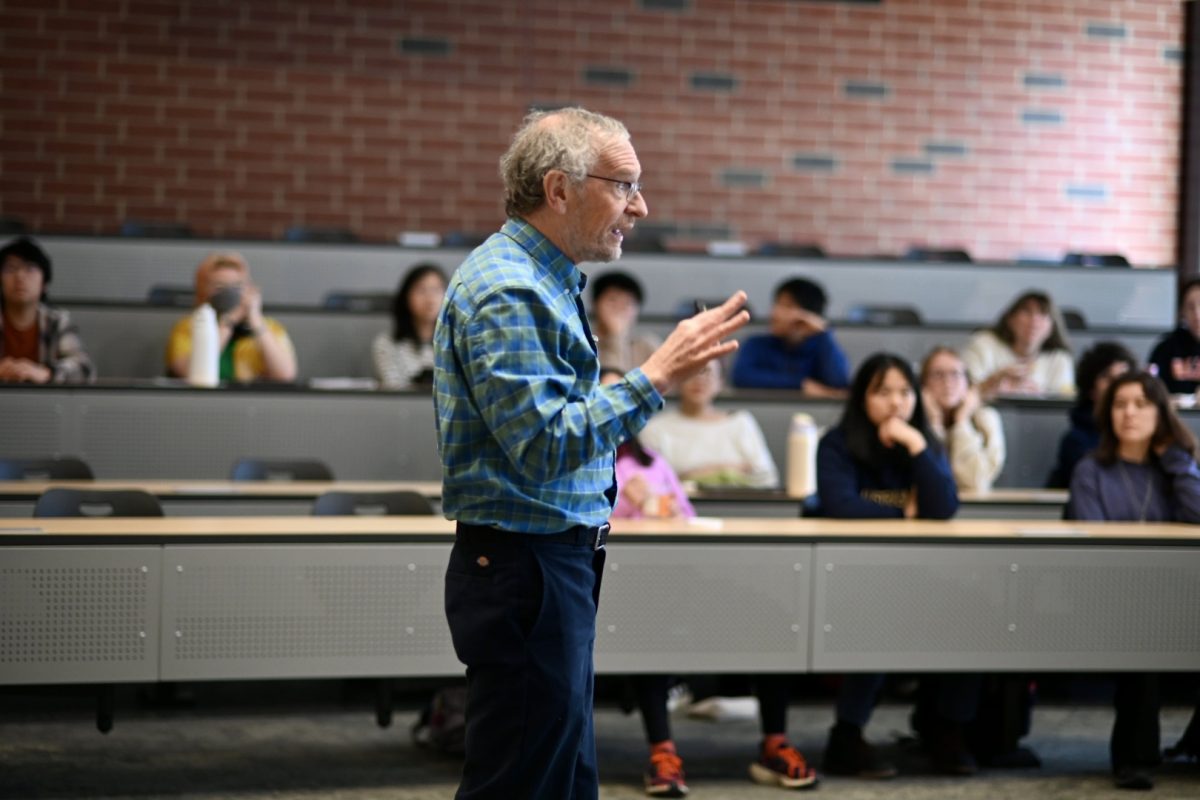

Brandi Robinson, a Penn State Energy and Sustainability Policy professor, attended COP28. She highlighted how the conference brought together countries facing wildly disproportionate impacts of climate change – leading energy-producing countries who are only beginning to feel the effects. Smaller countries nearing net zero are experiencing dire impacts now.

According to Robinson, the defining challenge of COP is finding consensus on agreements.

“Every delegation, all of the countries, have to agree to every part of the language,” Robinson said. “So try to think about getting 200 countries to agree on anything. Right? Good luck. You go find 200 people at your school and try to get them to agree on something, never mind it being as contentious and politically charged as climate change can be.”

“Initially, there was language in the agreement that explicitly mentioned the need to phase out fossil fuels. I think some of the most vocal opponents were Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Nigeria, and maybe Russia; they didn’t like the language at all. And it’s no surprise,” Robinson said. “These are big energy producers. Of course, they don’t want to hear language about phasing out one of their biggest sources of revenue. It took a lot of finessing and compromise, and that’s how these things work because it’s not a majority wins type of process.”

The final agreed-upon language affirmed a global “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science.”

The agreement, Robinson noted, “does still talk about the need to phase out fossil fuels, but it includes caveats that made some of these oil and gas producing states a bit more comfortable with the language.”

Many critics, however, don’t trust these agreements because of one simple reason: they say that the involvement of fossil fuel interests damages the conference’s integrity. In fact, fossil fuel representation has been the most controversial aspect of the conference, with it being the area given the most media attention.

For Donoughe, fossil fuel producers play an essential role at climate talks like COP28.

“I think they should have a lot of influence in talks like these because fossil fuel production is still part of our future,” Donoughe said. “Even as we bring green energy online, we need baseline fossil fuel production because wind and solar are not 24/7 all the time. We need that baseline production to keep our standard of living up. So when I see people talking about fossil fuels as the enemy, I think that they’re not getting the complexity of the situation.”

Robinson agreed that fossil fuels must be at the negotiation table.

“You can’t live in this world today without fossil fuels, and you’ve gotta find a way to be in the middle. I think this is where having a president representing oil interests was actually pretty useful,” Robinson said. “Without them being part of the conversation, this is just an Earth Day Festival. You’ll need the energy companies along for the ride to decarbonize the economy. We need to work together, not to be divided.”

Faulds views the annual COP meetings as a crucial forum. “The work that they do at these conferences is really important to setting the goals for where we need to be headed. Having them every year keeps everybody focused on the end goal, which is to keep temperatures below a 1.5 degrees Celsius increase of greenhouse gas emissions.”

The location and president-designate for COP29 was announced over the weekend, and it will be held in Azerbaijan and led by Mukhtar Babayev, a minister for ecology and natural resources with 25 years of experience working for the state-owned oil and gas company Socar.