How Voter Suppression Dismantles Democracy

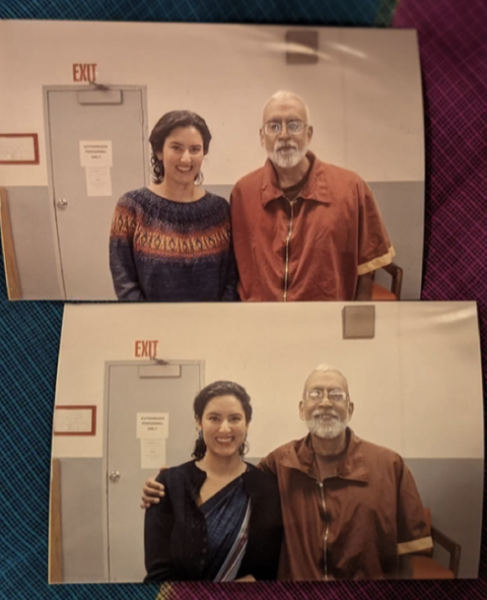

Early voters in Columbia, South Carolina, on October 6, 2020. Risks of COVID-19 only add to challenges of voting, making long lines for extended periods of time especially frightening.

October 28, 2020

With Election Day soon approaching, the threat of voter suppression is not imminent; it is already here. From the birth of our nation, electoralism has always been a flawed and messy system of democracy. Intimidation at polls, racially-biased election laws, and misinformation are all tools that have been weaponized against citizens of the U.S. We live in an age of rampant social media disinformation, a pandemic, and a president that has yet to agree to a peaceful transfer of power. When faith in voting is lost, so is the representation in government that democracy depends on.

Doubt in electoralism is especially apparent among the group with the lowest voter turnout in the country: young people. According to Bookings, only half of 18-29 year olds registered to vote showed up at the polls for the 2016 election year. U.S. youth voter turnout is on the low end globally, placing fifth to last at 46% according to the New York Times. Reasons for this can be attributed to many different factors.

Junior Clarissa Theiss, the acting vice president in student government at State High, recently took part in setting up a voter registration drive for 17 and 18-year-olds at school. As she volunteered at the drive, she saw firsthand the hesitation young people hold towards voting.

“Our generation is faced with a lot of existential crises that are going to come to bloom whenever we’re older,” Theiss said. “I think a lot of politicians, whether it’s the presidential or local election, don’t accurately represent what we want, regardless of their political affiliation.”

Theiss believes there are a lot of people attempting to make sure that the youth vote doesn’t make it to the polls. These attempts to suppress participation in elections come in many different forms and target more than just youth in America.

Since it became clear that 2020’s election would be one that depends on mail-in ballots due to COVID-19, President Trump has been laying seeds of doubt in the integrity of the outcome. The idea that voter fraud is an epidemic our nation faces is a baseless claim and intentionally tailored to claim illegitimacy in the event he loses. Through his influence in defunding the postal service and discouraging mail-in voting, he clearly shows that he believes less participation equals benefits for his candidacy.

A pervasive campaign of misinformation by Republican politicians to promote the false claim of extensive voter fraud was revealed by a New York Times investigation. This is a clear example of one truth: politicians invest in misinformation and thrive off of voter suppression.

Race and voting in the U.S. have always been intertwined in a disturbing and violent relationship. Stemming from the poll taxes and literacy tests adopted under the pretense of “racial neutrality,” racially biased election laws have disproportionately affected people of color. Data from a poll conducted in June of 2018 by the PRRI suggest that voter ID legislation has anything but a racially neutral impact. In 2017, a law passed in Georgia requiring that any names spelled with a slight error on registration documents be disqualified purged over 51,000 people from voting in the 2018 election, 80% of whom were people of color.

Beyond harmful legislation, harassment and intimidation is also a barrier to voting that non-white people have experienced. The 2016 election year was especially hostile for the Latinx community. Violent language and fear-mongering from Trump led to the dehumanization of Latinx people who faced a year that was uniquely difficult. According to a study conducted at PRRI, roughly one in 10 Hispanics said that the last time they or someone in their household tried to vote, they were bothered at the polls. Just two weeks before election day this year, the Trump campaign was sued by Mi Familia Vota Education Fund, a nonprofit group focused on Latino voter rights and participation, for alleged violent voter intimidation during early voting.

The process of voting can also punish the least protected among us: the working class. Election day is not a national holiday, and employers often don’t feel inclined to give time off to vote. Even during early voting this year, we’ve witnessed voters being forced to stand in lines for hours upon hours. For people living paycheck to paycheck, taking so much time off work is unthinkable.

Even if every single person eligible to vote did so successfully, the nominee with the most votes could still lose, as we saw in 2016. The electoral college is inherently an undemocratic system as electors are not required to vote in accord with the popular vote. The system encourages politicians to focus all their campaign efforts on the few keystone states that will decide the election, and neglect the rest. All of these factors lead to an inevitable result; many Americans have been disenchanted with the fiction of an equitable election.

“Since the White House, Congress, and Senate [are] made up of a lot of older people, it’s really easy to feel as though there’s not a place for our voice,” Theiss said.

Many young people especially are hesitant to vote for two candidates that they don’t believe will create the change they so desperately crave. For 16-year-old Theiss, if she could vote, she would jump at the opportunity.

“I have a lot of inherent privilege. The fact that I’m white, I’m middle class, I’m not struggling with poverty or anything,” she said. “I vote for people who would be impacted by the most serious policies. Maybe I don’t necessarily agree with one of the candidates, but they might be supporting something that’s going to make a difference to the kid who sits next to me in Bio class. I have a privilege to be able to say, ‘oh, I don’t know if I agree with that policy,’ and so I’m able to make that compromise.”

The extent to which the flaws in American elections disrupt democracy is something that cannot be ignored. A country enveloped in suppression is a country in decay that robs our most marginalized groups of their fundamental rights. Without a drastic upheaval of how they are run, citizens will continue to be disenfranchised every four years as they have been for the past two centuries.

Jacob Wittrig • Oct 28, 2020 at 4:31 PM

I think it would have been helpful to include party percentages in reference to mail-in ballots. Currently the rate is about 3 Democratic votes for every Republican vote, so Trump has an incentive to stop this form of voting.